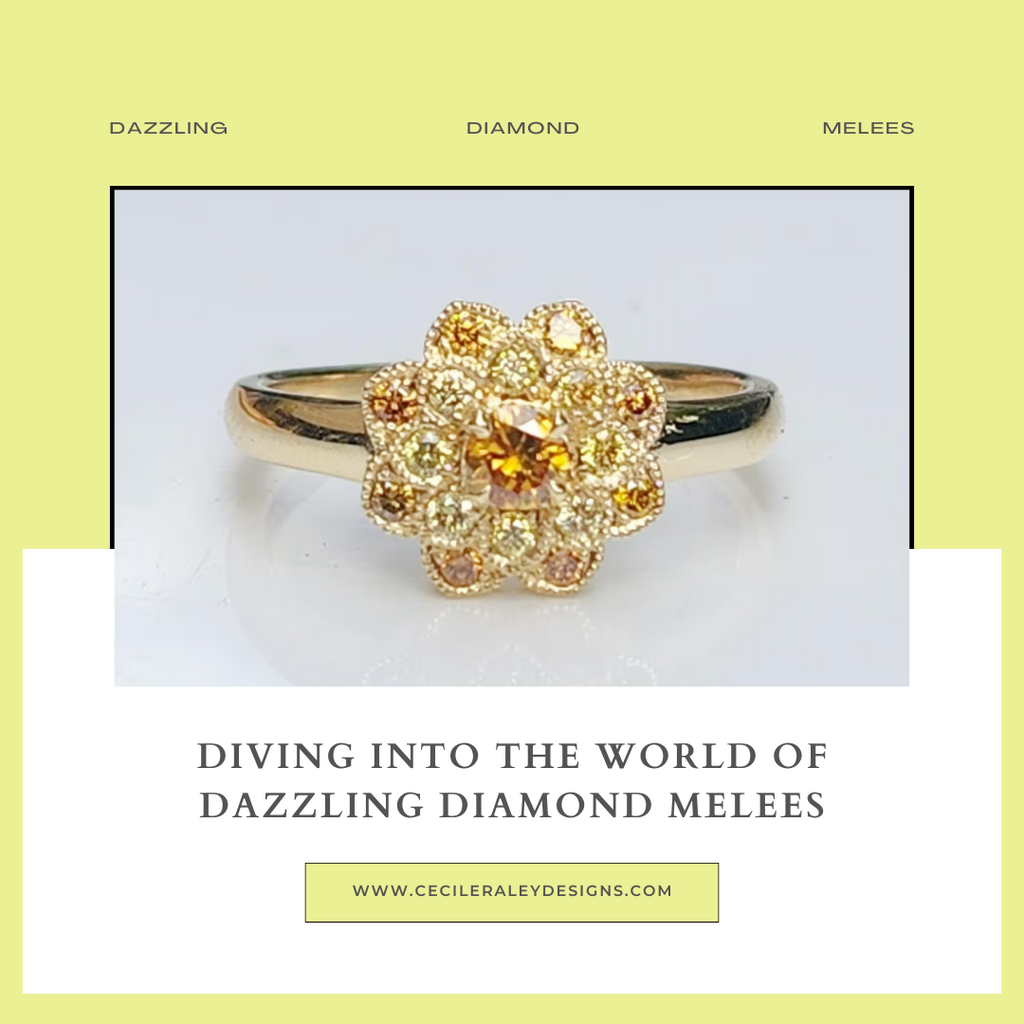

Diving into the World of Dazzling Diamond Melees

A recent sales analysis of my shop confirmed something my readers probably already know: I make a large quantity of my sales volume by selling melees (half my Etsy sales are melees gems). My best-selling small gems are sapphires, spinel and Paraiba tourmaline, but colored diamonds are also making a comeback in my shop. By this, I mean natural-colored diamonds, and in particular, those that are more reasonably priced. Surprisingly, using natural diamond melees can be cheaper than many gemstones. It is cheaper to set sapphire melees or non-neon spinel colors, but ruby, paraiba, hauyne, cobalt spinel to name just a few, will cost more than a diamond.

There is a vast price range when it comes to natural diamonds. There’s a more expensive and a less expensive spectrum:

Blue, red and pink: these are among the most expensive gems your money can buy; fancy pinks in 3mm sizes now command over $40,000 a carat wholesale.

However, there’s a cheaper color spectrum, and it also has a lot of interesting tones. Here, I would include yellow, orangey-yellow, greenish yellow, brownish yellow. I would also include brown and champagne diamonds here. These cost the same as white diamonds, and if you like lightly included champagne or brown diamond material those are even cheaper. Let’s break out this category a little more.

Green diamond: most of the green spectrum that is affordable in price will have a yellowish tint and thus look olive colored. They cost about the same as lighter yellow diamonds. Cold greens (what GIA calls a straight green to a blue green), if natural, are out of the question price wise.

Yellow diamond: those will fall into four categories with GIA: Vivid yellow, fancy intense yellow, fancy yellow and fancy light yellow. I think the light yellow is too light and vivid is overkill. My recommendations are in the middle. These will cost you 2-4x the price of regular white diamonds.

Brown spectrum: what the trade calls golden yellow will fall into this, as well as some of the orangey tones that are not really orange but more brown (like the color yellow orange), plus cognac and chocolate colors. The standard brown tones cost less than white diamonds, the orangey tones cost more, but unless it is a true orange they cost less than yellow diamonds.

This chart illustrates some of the GIA diamond hues in various spectrums. You can see it on their website here.

This article by GIA provides more details regarding how they describe colors: https://www.gia.edu/fancy-color-diamond-description. If a diamond does not fall into the D-Z color scale (colorless to champagne), then it is considered a colored, or a fancy diamond. Generally, the more vivid the color, the higher the price (brown diamonds are the exception).

And what of those nicer neon (teal colored) blue diamonds that look so pretty? Those, and many other brighter colors, are irradiated. Irradiated colors include greens other than olive (like apple and forest green), lemon yellows (cool toned canary yellows), reds, and stronger, cooler pinks. Irradiated diamonds are not harmful, and they can be significantly cheaper than natural diamonds. We do not use them at CRD but they are fairly common and accepted in the trade.

If you like incorporating the natural-colored tones into your designs, however, here are some tips for you.

Inclusions: with natural-colored diamonds, the industry can be a bit more liberal with inclusions, and not all diamond melees are finely graded down into the various clarity ranges. This also has to do with the fact that colored diamonds are far rarer than white diamonds (assuming the diamonds are untreated and not lab diamonds either).

Matched sets: due to the rarity of colored diamonds, it is harder to match them. This is especially true of the green tones. With the standard yellows, there’s more available quantity.

Design: the colored diamonds along the yellow spectrum I have described are all warm tones, so they are not easily combined with just any other color. But there are some interesting color combinations that I can suggest.

Fancy yellow diamond and Paraiba tourmaline, or hauyne, or cobalt spinel. Yellow and blue look great together. Blue zircon and sapphire are also a nice combo, as is teal blue.

Fancy yellow to golden and Russian demantoid. That is a very appealing combo to me, especially if you include another similar stone: sphene. These would also go well with olive green diamonds.

Golden, orange and red tones. All these combine well together. I suggest warm reds here like Mexican fire opal. Or a more contrastive pinkish red but then the diamonds cannot be too orange. Golden and pink can look fantastic together.

Yellow and orange toned diamonds with purples (sapphire for instance) or pinks. I like soft pinks here, and strong purples, but it all depends on how much brown there is in the diamond. I would combine stronger brownish hues with softer pinks, and more open yellow tones with strong purple.

Naturally, we can supply any of these diamonds for you if you are interested.

Continue reading

See in store

See in store  See in store

See in store