Adventures of a Broken Foot: Namibia

I didn’t advertise my upcoming trip to Namibia because I had been forewarned. Yes, Namibia has a wealth of minerals just like most other African countries. In the gem trade, it is well known for its gorgeous blue and blue-green tourmalines, for example. But at this time, there is little to no production. Most of what is on the market dates from 10-12 years ago. The material is surely in the ground but at this time there are no larger ongoing mining projects for gems (there is some production near Karibib). There’s lots of ore production (copper, iron, zinc) and at times these yield bi-products of minerals, but as far as I was able to ascertain (and also confirm on site), the small amount of minerals and rough gems that come out find their way into the market through private hands. But more about that later in this blog – or the next one. I’m a chatty blogger, as you know. I always have a lot to say, so you gotta hang in there and read!

Let’s, therefore, start at the beginning. Last summer, my travel and gem hunting buddy, Jochen from Jentsch minerals, asked me to join him on his second – and last – trip to Namibia. He’s turning 80 in October and revisiting this beautiful country was on his bucket list. Back in 1966, when he was just 22 and working on his masters in geology, Jochen traveled to Namibia in search of minerals and adventure.

Namibia, in brief, was a German colony from 1884 until the end of WWI (1914) when it was controlled by South Africa. Namibia gained its independence in 1990, and it ended apartheid the same year. Namibia is now a peaceful and very modern country, perhaps the most modern in all of Africa. It derives much of its income from tourism due to its plentiful wild animals and national parks, as well as its unique geography: it has the largest coastal desert in the world, as well as beautiful canyons and red rock formations reminiscent of the American South West. And as mentioned above, Namibia also profits from its wealth of natural ore. A German geologist told me about projects under way for Namibia to increase ore production, but also learn how to manufacture metal for industrial use with these minerals so that more of the mining profits stay in the country.

In 1966, Jochen arrived in the capitol Windhoek after a 3-day flight from Germany with stops in Spain, Angola and South Africa, and then made his way north to the famous Tsumeb mine by riding a local train for 22 hours. We made the same trip by car, and it took approximately 4 hours, so you can imagine the speed of the train back then.

Now known as the Ongopolo mine, Tsumeb was discovered in 1893 and remained open until 1990 when it closed due to flooding. Attempts were made to pump the water out but they were unsuccessful.

The Tsumeb mine produced copper, lead and zinc (among other metals), but among collectors it is mainly known for its wealth of extremely rare minerals – over 240 different minerals, in fact. 55 of these are totally unique to the mine and have not been found anywhere else in the world. Among the more well known minerals found are gorgeous specimens of dioptase, azurite, calcite, wulfenite. Many of the finds are now in museums all over the world. No wonder, therefore, that the mine attracted Jochen’s attention, and he desperately wanted to explore it himself.

By a tremendous stroke of luck, the geologist that had previously analyzed the mineral samples had quit, and the person in charge offered the job to Jochen. He stayed in Tsumeb for five weeks! Each day when his shift ended, Jochen was allowed a couple of hours in the mine to find specimens; and this is how he started to scale up his collection. Had Jochen stayed in Tsumeb, he told me, he would now be a millionaire. Fortunately, money isn’t everything!

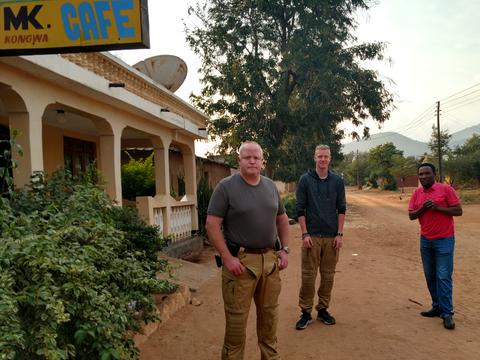

Anyway, Jochen had always longed to return to discover the rest of the country, and I am always up for adventure, so I joined him with great pleasure. Our third companion was another collector and hobby geologist, Klaus K., Jochen’s best friend.

We arrived in Windhoek early on a Friday morning from Frankfurt and headed straight to “Savannah Autovermietung” where we had rented a Toyota 4x4 with roof tents and full camping supplies. I’d recommend them to you but while their cars are in good shape, their roof tents are a mess. First, we almost lost a bracket because it was screwed on with a makeshift screw that didn’t really fit, and later in the trip when I was already in the hospital, one of the rails that held the tent broke in half and cost Jochen and Klaus 2 days of their trip to get it soldered. So Savannah is a no go.

We spent the first day in Windhoek at a tiny ‘hotel’ aptly called Tourmaline guest house that I do recommend: it had just four rooms overlooking a pool, free breakfast and mongoose visits for $25/night. We ordered food delivery for dinner just like in New York (Thai food, even), relaxed on our veranda. Saturday, we headed north.

Contrary to most Sub Saharan African countries, the main roads in Namibia are mostly paved. And even the gravel roads are very passable, leaving clouds of dust as they passed us going above 50mph. This made our travels so convenient that Jochen actually complained. “No driving challenge,” he said. But he’s been to Africa 300 times, I’ve been to Africa 3 times. I thought it was just fine.

Contrary to most Sub Saharan African countries, the main roads in Namibia are mostly paved. And even the gravel roads are very passable, leaving clouds of dust as they passed us going above 50mph. This made our travels so convenient that Jochen actually complained. “No driving challenge,” he said. But he’s been to Africa 300 times, I’ve been to Africa 3 times. I thought it was just fine.

We did get to face a challenge, however, just not one Jochen intended. An hour north of Windhoek, we were stopped by the police. The officer took a quick look inside the car and spotted Jochen not wearing his seat belt in the back. “This will cost you N$1000, and our receipt book is finished, so you have to drive back to Windhoek to pay,” he said. Shit.

Well. This is Africa. So we figured, let’s try the African way. “We would love to get to Tsumeb today,” Jochen responded. “I used to work there, back in 1966. This is a trip down memory lane.” “Is there anything you can do to help us?” I added.

The officer paused and then asked if we had N$500 in cash. We did. Of course. Five minutes later, we were back on our way. This is Africa!

Why am I saying this? Because Africans say it. They know their way is not that of what we call the West (no, Europe is NOT west of Africa). Labor is cheap because it is plentiful, and correspondingly most wages will not be sufficient to live on. A regular worker will make anywhere between N$1500 and perhaps N$6000 per month ($75-$300). A restaurant meal in the boonies is N$100, a doctor’s visit N$250. A typical supermarket bill N$500. Therefore, charging tourists more for a taxi ride, asking for money when pointing the way, and yes, negotiating out of a traffic ticket by requesting cash are a way of life. And a necessity for many. I do not always like it, but I no longer judge it.

Less than three hours later, we arrived at our first geological stop to admire the world’s largest meteorite. The Hoba Meteorite, as it is called, is a big, shiny, black hunk of metal weighing 130,000 pounds. Found in 1920, it was so heavy that it has never been moved from its impact site. It landed exactly where it is now about 80,000 years ago and at the time, it annihilated everything within a 20-mile radius. It did more damage than Hiroshima, Jochen explained to me. I’m including some pictures, but if you aren’t a geologist, I’m not sure it is truly worthwhile checking it out.

Our next destination was Tsumeb. The town itself had lost its bustle but as a gateway for tourists heading into Etosha National Park, it provided great accommodations: the ‘Minen Hotel’ has a 100 year history. It offers modern accommodations, lush gardens and a pool, as well as excellent German and International cuisine. The rooms were less than $50 per person, and my fantastic T-bone steak was not even $10. Last time I had anything this good I paid $60 in Manhattan.

Early the next morning, I accompanied Jochen on a trip down memory lane. We located the old open pit and the mining shafts, taking some pictures. The main strip was devoid of people on a Sunday, but the local gas station turned out to be the hangout both for passing tourists like us as well as locals looking to chat with you and beg for cash or food to get through the day. The latter is commonplace in Africa and needs to be understood for what it is. People are poor and needy, they have to ask, they mean no disrespect. Of course this can feel scary or pushy but it need not be. Sometimes we give something, other times we clearly say no. Namibia has among the largest white populations in Sub-Saharan Africa, approximately 30%. But the white people have over 90% of the money. Economic disparity among racial lines is commonplace.

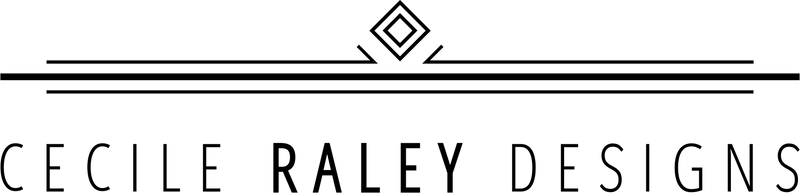

After we supplied ourselves with a full tank of gas and several bottles of water, we started north for Etosha National Park. Etosha is now Africa’s largest national park, with Tanzania’s Serengeti coming second. Contrary to Serengeti, you can drive through Etosha without needing to hire an expensive touring company. In addition, the entrance fees and overnight lodgings are a fraction of the cost of Serengeti. In fact, measured by the Euro or American Dollar, everything in Namibia is extremely affordable.

Most of Etosha’s camp sites also offer lodges, a restaurant and a pool. At Halali camp, our overnight stop, we spent the evening watching the animals at a watering hole, watching various groups of animals taking baths in succession based on rank. The elephants went first of course; they were later joined by 8 or 9 rhinos – a rare site for African parks. The zebras and gazelles kept a safe distance but circled the area until the rhinos were done, then they took their turn having fun. We watched during sundown, sitting in total silence so not to disturb, enjoying the elephants spraying their offspring and enjoying themselves. We then went to the outdoor restaurant for dinner: Kudu (antelope) steak with pepper sauce and potatoes.

Our next destination was the famous Namibian desert. Our trip took us through an impoverished small town by the name of Khorixas, then to a gorgeous campsite in between red rock formations. We reached it just before dark. It is important not to drive in the dark, especially as a tourist because there are no street lights and animal crossings. You may run into an antelope, or even a giraffe (though less likely).

The camp was nestled between red rock formations reminiscent of the Arizona desert, which brighten up at night. The main lodge sits on an elevation and has a pool from which you can watch the sunset with the house cat and dog keeping you company. The dog, whose name I forgot but whose memory will stay with me forever, will become the protagonist in adventure of my left foot.

We decided not to set up our tent as it was late, and take advantage of the ‘glamping’ alternative instead. For $13 per person, we got to sleep in one of the lodge’s tents, fully furnished with beds and nightstand, table, chairs; and outside a patio complete with fireplace, even a sink with running water, and electricity. A brick outhouse with a shower, bathroom and warm water completed our setup. The water was heated by coal ovens that were started at 7 a.m. We had electricity and even a USB port next to the bed. For dinner and breakfast, we had the option of eating at the main lodge ($5 per meal).

The next morning, we set out to find a copper mine by the name of ‘Mesopotamia’. Our research suggested that it was the source of unusual bubble shaped opal crystals that Klaus wanted to buy. Guided by a young Damara woman named Tanya, we drove the 30 miles across small and uneven dirt roads into the Tundra. Shortly after passing a date farm we arrived at one of the dumps from the mine and stopped to look at the rocks. Mindful of the plentiful local snakes, we started looking through the rocks and chopping some of the more promising ones apart. We didn’t see the bubbly opal formations we were looking for but found lots of malachite as well as turquoise mineral that looked like chrysocolla and azurite (subject to confirmation by a lab as any visual analysis will get you only so far).

We gathered some of the nicer looking material and loaded it into the car. Then we headed another mile or so down the road until it ended at a group of makeshift buildings behind which, alas, we saw mining pits. A group of workers directed us to their supervisor, a small middle aged Chinese. We showed him the images from our mineral book. “Only find one time,” he explained in broken English, showing us two rather low grade rocks with the bubbly formations we sought. “Copper only but work stop because no water.” Indeed, water is a very precious resource in Namibia and uninformed tourists are always asked to be mindful. (At one point, Jochen and Klaus even donated 20 liters of water from our tank to a woman living in the middle of nowhere who helped them find another mine. She was eternally grateful.)

While we were skeptical that there was no opal, we decided to turn back. Often, the claim that nothing was found just boils down to there being nothing for sale. Quite possibly, there were other buyers before us, or the supervisor already has clients for it. After all, any collector’s minerals are bi-products, so the owners of the claim don’t have any interest in it and so this stuff wanders off under the table.

For the second night at our camp, we decided to do a practice run at setting up the tents, and after a swim to cool off from the 100-degree temperature, we enjoyed a dinner of fried and breaded Kudu (antelope) at the lodge.

Much to my surprise, I had a great night’s sleep in the tent. The 4-inch mattress was cushy, and the desert gets cool at night, even in summer, so when I woke up at around 7 a.m., the air was fresh and cool. Klaus was already making breakfast on the gas cooker: fried ham and eggs with sliced peppers and German rye bread. Jochen prepared coffee, and I supervised from above.

Before packing it in, I decided to take a short jog to the lodge for the Wi-Fi. I didn’t make it there, however. And what happened next changed the entire trajectory of not just the day but the entire trip!

I was in a slow and relaxed jog, enjoying the air, when the lodge dog darted out of the yard to greet me. He was wagging his tail so hard that his entire backside was moving. “I know you want to play with me,” he was saying. For whatever reason, I thought he’d run around me, and I do think that’s what he intended. I was so wrong. And so was the pup. Because his bum hit my left leg just as I had lifted it, and I took an accelerated dive over his behind, landing on my left shin and ankle.

I was more surprised than anything. I crash on my bike at least twice a year, I’ve jumped off slightly higher elevations while bouldering, and I regularly work on my reflexes by jumping off a wooden box in the gym. My late friend and coach Sebaj had left me the legacy of being strong and agile, with fast reflexes and sturdy bones. For eight years he trained me, relentlessly and often against my will, 3x a week. In 2020 when the gyms were closed, we trained at my house and started road biking together. He was a powerful sprinter, a local legend in NJ.

Well, Sebaj, I’m really sorry I disappointed you, wherever you are. I took one look at my displaced ankle and I knew it had to be broken. “Not good.” I thought. But I was calm and collected. My strong suit during an emergency. Total focus, decision making part of the brain fully on.

It didn’t hurt (then) but I decided not even to try to get up. “Jochen, Klaus,” I called, “something’s happened, I need help.” At first they didn’t come, I must have sounded way too, um, ‘normal’. I tried again, adding urgency to my tone: “I’m not kidding, I need help.”

Klaus jogged over, and right away I saw the worry in his face. “I think that’s broken,” he said (yeah, no shit). Stay put. Klaus was an EMT for a couple of years, and he took three semesters of medicine during his studies for his masters in sports science. When going to Africa, he and Jochen are always well prepared, because, as I am currently illustrating, when you are in the middle of nowhere and stuff happens, you are on your own.

Klaus dashed back to the tent and returned with two folding chairs, water and an 800mg tablet of Ibuprofen, Jochen in tow. They heaved me onto the chair, elevated the foot, and our German tent neighbor stood watch in case I’d pass out from the drop in blood pressure from the shock. My fingers were indeed getting cold and I was a wee bit dizzy.

And then? Well, the next step is to have a plan for the next step.

Which was? I will tell you in my next blog.

Continue reading