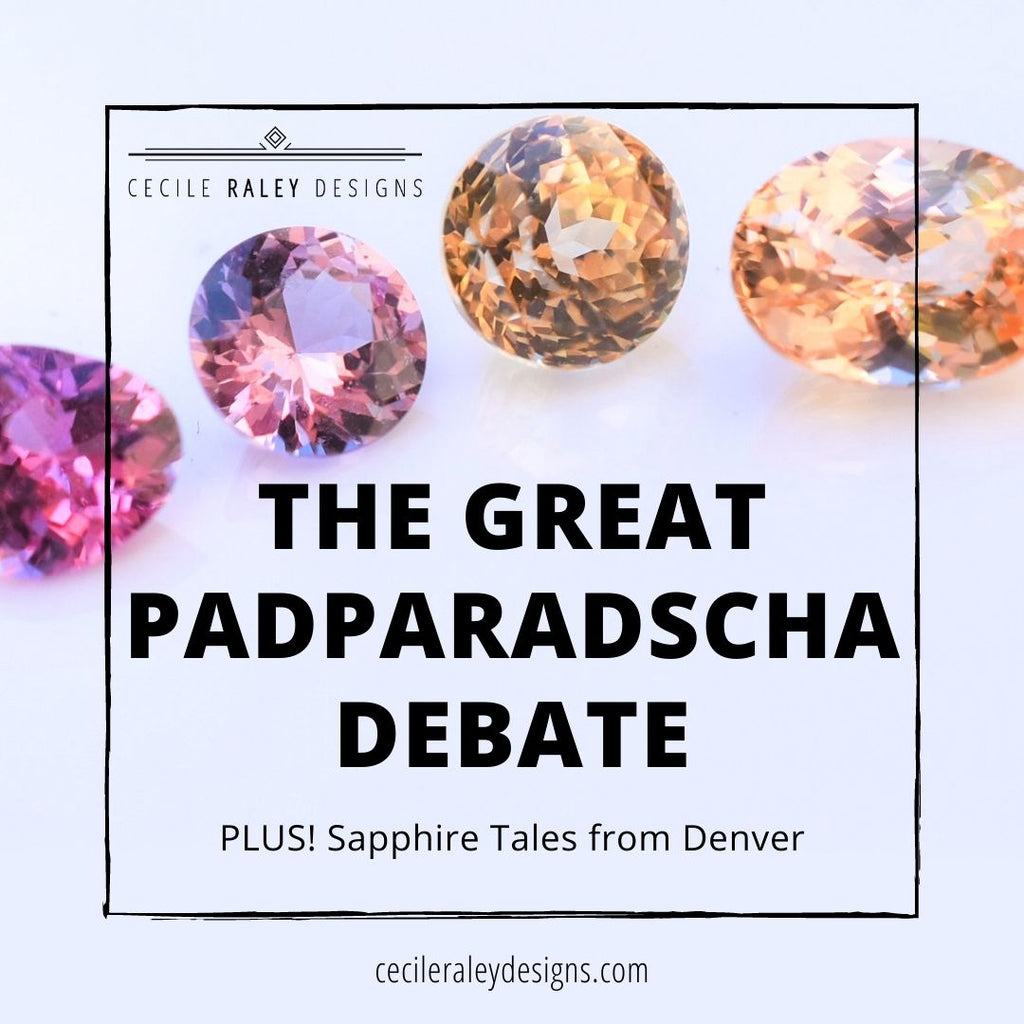

The Great Padparadscha Debate PLUS Sapphire Tales from Denver

The May Denver gem show is actually fairly tiny, even during non-covid times. But with nothing else big coming up until late August and September, I decided to go anyway. A few days away is always refreshing, especially when it involves looking at gems.

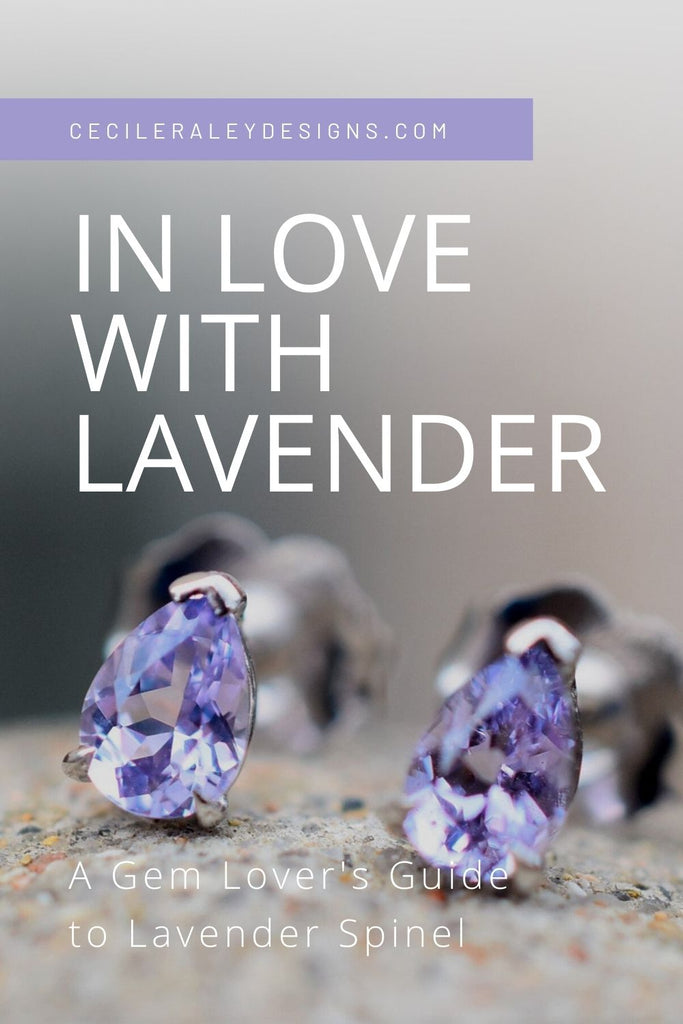

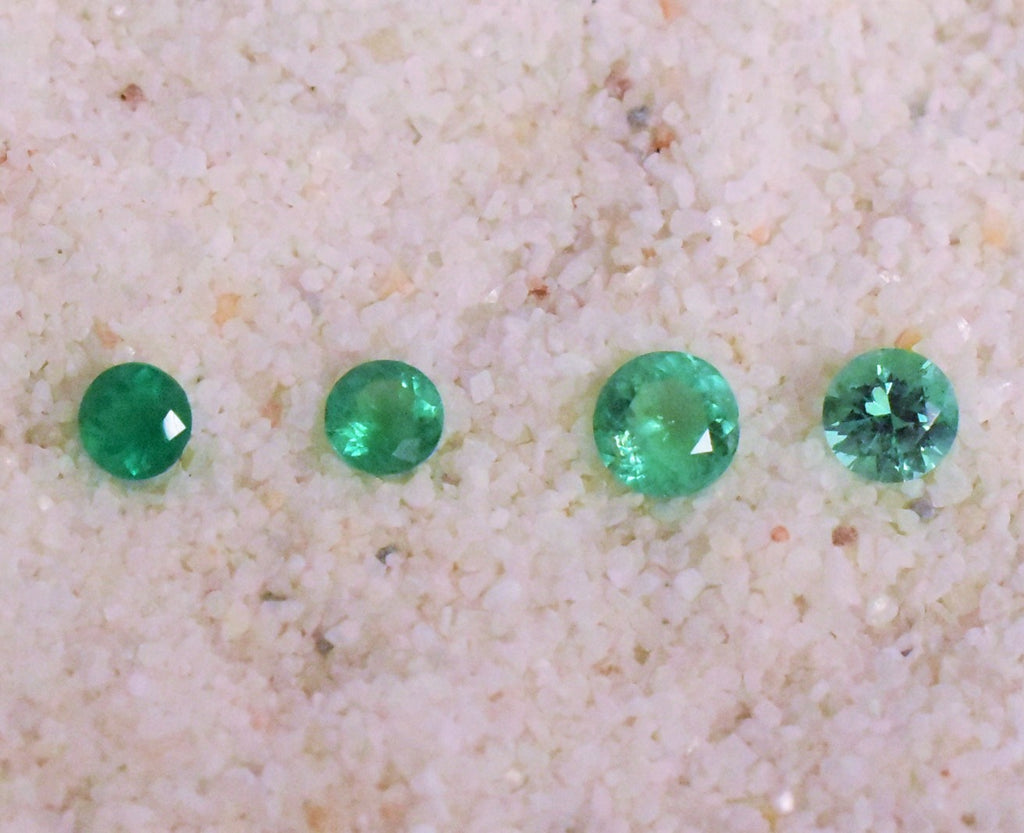

If you checked out my recent videos, you’ll know that I made at least a few scores: several small parcels of lavender and peachy lavender melee gems from Madagascar, some silvery lavender Vietnamese spinel and lavender sapphire matched pairs (a few of these will make it into the stud earring section), as well as a few more Russian emeralds.

My main focus this time, however, was to secure more larger sapphires for the shop, and potentially for some showy jewelry. I found some heated and unheated blue ovals, rounds and pairs, as well as some orange-apricot tones that I found unusual – some of these will get a mini cert to show that they are unheated before I post them.

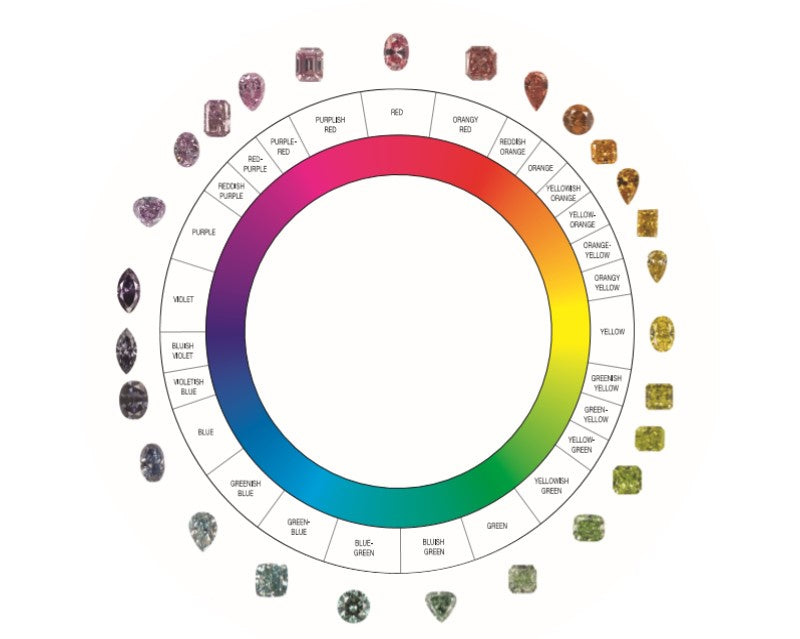

The apricot colors I got would not qualify as padparadschas because they contain too much orange, but for those of you who prefer to have a not quite pad that’s really a pink sapphire perhaps these gems are of interest.

As you may or may not know, certifying padparadschas has become something of a nightmare to buyers and sellers alike. AGL has decided to subject all pinkish orange sapphire candidates to a color stability test, and most gems do not pass it, thus not making the coveted pad label. This test has entered the gem labs world after it was discovered that orange pink colored sapphires from Bemainty near Ambatondrazaka, Madagascar, turn pinkish after a few weeks of daylight exposure. The color reverts back over time, largely speaking, though I’ve spoken to some vendors who feel that not all gems regain the intensity they once had and object to a color stability test on those grounds.

AGL reproduces the color stability test by a 10 minute exposure to short-wave UV radiation, and in conjunction with very strict color guidelines, classifies sapphires as just pink or some other non padparadscha color, even if those sapphires have received the pad certification from GIA, GRS, Dunaigre or any other combination of laboratory certificates. It has even de-classified previously certified padparadschas from their own lab, as well as some sapphires that are of Sri Lankan origin. As a result, many vendors, retailers, and some retail buyers are no longer sending any padparadscha candidates to AGL. I should note that AGL is not the only lab applying the color stability test, but it nonetheless appears to have the strictest pad conditions.

Here’s an interesting article by Chris Smith from AGL with more detail, if you are interested.

While padparadscha sapphire is not a specialty of mine, this is an additional reason why I don’t carry many (or any, for that matter). The "pad" label is now so highly prized that it can easily overprice the gem. True padparadschas are beautiful indeed – even to my eye, and I clearly prefer more vibrant colors. But that does not mean they are worth the headache or high price, unless you have very deep pockets and just don’t care.

Here are some more orange-apricot gems that, paired with more lavender colors and perhaps set in yellow rather than rose gold, would make a lovely addition to a collection without killing the piggy bank: sapphires from left to right: two unheated peachy-pink Madagascans (too pink to be "pad") and two unheated Sri Lankans (too orange to be "pad")

Here is a closeup of the right-most orange-apricot sapphire featured above:

And here are a few videos from my YouTube channel featuring some more sparkling treasures from Denver:

Continue reading