Adventures of a Broken Foot: In the Middle of Nowhere

As you read in my previous blog (you didn’t? Go back!), a playful dog plowed into my left leg as I was jogging to the lodge at our remote camp site near Khorixas, Namibia. A hard landing later, I found my foot twisted out of place. Kaput.

What next? After my friends Klaus and Jochen had safely stashed me onto a chair and raised up my foot, we quickly hashed out next steps. Jochen hurried over to the lodge to inform the owner and ask about medical transport. Unsurprisingly, the latter proved unavailable. We had to get to a clinic ourselves, and this entailed a 45-minute drive back to Khorixas. Klaus folded down the roof tents, and after a half hour they pulled the car up next to me to load me into the back seat, resting the broken ankle on a pillow surrounded by cold water bottles to cool it. Klaus placed a wet paper towel over the top of the foot to further reduce the swelling. I had already popped the strong ibuprofen. I took photos of the ankle from various angles.

We then pulled up to the lodge so I could catch enough Wi-Fi to call one of the most important people in my life, Dagmar. Dagi and I lived in the same building when we were little. We met in the sandbox, were inseparable as kids and have remained close our entire lives.

Dagi is my own personal angel. If you had a Dagmar, your life would be better, because Dagmar makes everything better. She’s a pediatrician, and – trained at the renowned Mayo clinic in Wiesbaden, she’s also an excellent diagnostician. She helped me solve various of Sebaj’s cancer-related emergencies from afar, she’s been at my mom’s side when she died after a seven-year battle with Lou Gehrigs and Aphasia in 2021, she takes care of my sister, my 20-month-old niece, and of course, she takes care of me.

Dagi picked up her cell in the middle of a patient visit because she knows if Yvonne calls during Dagi’s office hours from Namibia, there’s a problem. “Broke my ankle,” were my first words. “You sure?” “Yes, I’ll send pix. We’ll be heading to the closest clinic but there’s no advanced medical care here.” “Got it. How long does it take you to get to Windhoek?” “About five hours drive.” “Ok, by the time you get there I’ll let you know what’s next, have the clinic stabilize it.” “Ok. Ta.” “Love you.” “Ja.”

The camping lodge owner had advised us not to go to the hospital in Khorixas (not very good she said) but to stop next door at a small private clinic. So off we went down the dirt road and onto the main gravel road at the top speed Jochen, the most experienced driver of our team, deemed safe.

The clinic was in the center of town, which constitutes a gas station and a strip mall with a furniture and clothing store, as well as a supermarket; nothing more. At the clinic, my friends were stopped with the words “N$250.” ($13). Money first, then treatment, that’s how it is in most developing countries, otherwise the clinics cannot survive and then medical care goes from little to none. We were later told that there are free as well as very low-cost services available but their availability and what these entail is limited.

I got pushed into the clinic on an office chair with a broken wheel. I could have hopped faster but that was deemed too risky with that dangly ankle. There was no wait (N$250 is quite a door stopper for locals that make between N$1500 and N$3000 a month), and the doc who introduced himself as Patrick, saw us right away. “Most likely broken,” he said. Uh-huh. “Go next door to the hospital and get an X-ray, then bring it here. I don’t have a machine. But don’t have them attempt to set it or do anything else.”

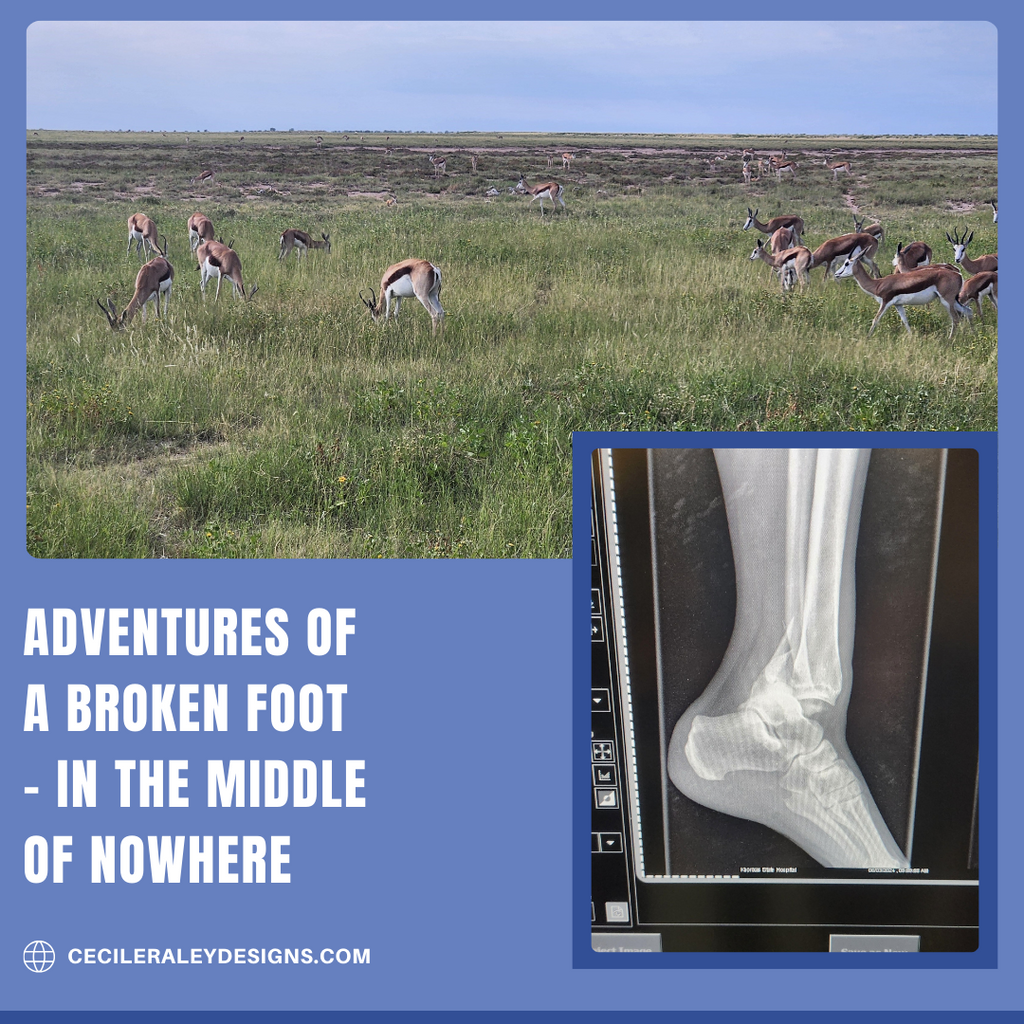

The small hospital was right around the corner. “N$150” was their greeting, to be settled before any services of course. Klaus and Jochen settled the bill while I was wheeled into X-ray with a real wheelchair. It was quick and efficient. The X-Ray, a Siemens machine, just the printer was broken. (So we took photos of the screen.)

Despite my expensively purchased Verizon wireless plan, internet was completely unavailable in Namibia, but the doc hooked me onto his iPhone so I could send the images to Dagmar. He also put a plaster cast around the lower part of the foot, ankle, and up the calf, leaving it open in the front. He closed it up with a bandage. I asked for a heparin shot to prevent clotting, and the doctor agreed. (The N$150 we paid on entry ($7.50) covered everything).

Images in hand, we headed back over to the clinic and showed the images to Patrick. A clean break of the lower fibula, was his assessment. And a piece of the ankle had broken off as well. The temporary cast should be ok he thought (but I saw in his eyes that he didn’t love the job). He loosened the bandages a little as I could already feel the swelling pushing up against the plaster.

We then dashed off in the direction of Windhoek. The first hour of the drive I was ok, but then the foot started throbbing. Pins and needles in the toes, and pains shooting up from the ankle to the lower leg and calf. “No pressure against the bone,” Klaus said. “And too much swelling.” I took another Ibuprofen but it didn’t do a thing. Four hours to go.

What next? My pain was climbing up the ladder. A 7, I decided, not a lot of room at the top here. “Jochen? You brought the morphine, right?” He did. “I’m gonna have to take one.”

Story detour: about 18 years ago, during the gem shows in Tucson, Jochen contracted a dangerous and extremely painful bacterial infection in his lower back (he was in organ failure when he arrived at the hospital but after 6 months of recovery he was 99% back on track). Jochen was prescribed morphine for the pain, and he saved what he didn’t need at the time. The morphine is always in his Africa emergency pack, for precisely the types of situations we were now facing, as well as for the one you don’t want to ever experience: ending up somewhere on your own and without transport, facing death by thirst or starvation while injured.

I took 15mg – the lowest dose – with a big swig of water. Hydration is key and also helps to dissolve the pill. I should have chewed it for speedier absorption but I forgot. “It’ll just take 20 minutes,” Jochen offered. I disagreed, having watched Sebaj suffer with nerve pain for up to 60 minutes, waiting for the stuff to kick in. “I’ll put it an hour,” was my response. We could do a bet. I was gonna need distraction.

Klaus rubbed my upper leg lightly upon my request, to distract the nerves. Jochen entertained with stories about his previous trip to Namibia, while I worked on my breathing. 4 counts in, 4 counts hold, 4 counts out, 4 counts hold. Meanwhile the pain worked its way up to an 8 or 9.

After 20 minutes it eased a little bit, but it didn’t get bearable until minute 40, and by minute 60 it was gone. (Of course I was counting the minutes). As expected, my mouth went dry, my appetite disappeared, and I became rather chill and relaxed. All are well known side effects of morphine.

Next problem. I really really had to pee. An average bladder holds about a liter, I heard. Mine was on the verge of overflowing. (When did I drink all that water??). My left knee was resting on an empty milk container, which in turn was propped onto our guidebook so I could get my leg into an angle that made for minimal pain. I pulled the container out and asked Klaus to cut the top completely open. We stopped at a rest stop, I slid out of the car, my bum resting against the back seat, and I put the container between my legs. Aaaaaaahhhhh. Let me tell you, I so did not care that I was with two men, neither of which I am in any way intimate with. I just had to go. I put the container on the floor, pulled up my hiking pants and offered the honor of emptying it to Klaus. He complied, with a grin. You gotta take this shit in stride.

We reached Windhoek by 6 p.m. My phone offered 3 bars for roaming (finally) and I called Dagi again. “Lady Pohamba Hospital please.” “Ok, bye.” Dagi’s Namibian friends had advised that I go there. Lady Pohamba is a private hospital, completely operating on Western standards, inclusive of accreditations, equipment, and nursing rotations.

Just in time. The morphine was wearing off. Payment getting sorted (first), this time N$60,000 as pre-payment, to be credited back if not used up. I was then wheeled into the ER and received immediate medical attention. The pain was climbing up the ladder, hastily making its way into the dreaded double digit: the TEN. I resorted to breathing used for birthing (or stretching, by the way), deep breath in, loud and long breath out. I grabbed the nurse’s hand. “We’ll put in an IV and give you Paracetamol,” she told me. “That will not do,” I said. The attending doc agreed.

“Ketamine,” was her view. “Then we open the cast and set the foot. After that you will feel a lot better.” Dagi on speaker, phone resting on my belly, this was confirmed as I explained between long and shaky breaths, apologizing for the “ddddddddd-eeeee-lay.” My entire body started to shiver, my hands went cold. I was still talking, and as the docs told me later, I never stopped the entire time. I have no idea, by then I had passed out. From the ketamine, the pain, who knows.

I was kept for observation for two nights, supplied with lighter pain meds, IV drip; and a South African orthopedist by the entertaining name of Willem Moolman came to check on things twice a day. A CT confirmed the break but also showed a third fracture, making the break “as bad as it can be” in Doc. Moolman’s ‘soothing’ words. Gentle bedside manner, making everything sound better than it is, and being cautious with information is an American medical cultural trait, borne from the necessity of having to avoid giant lawsuits. The rest of the world is a little more blunt...

The CT also showed a lot of swelling, and that makes medical work inside an ankle very messy. Doc Moolman suggested waiting for the swelling to go down, which could take anywhere from 4-5 days to 1-2 weeks. Then I would need screws on one side of the ankle, a plate on the other, and I’d be in a moonboot off that leg for six weeks. Yuckles. “I was welcome to stay,” he said, but it really wasn’t necessary as long as I continued giving myself heparin into the belly (it’s just like insulin shots), took an anti-inflammatory and kept the leg elevated.

At $500 a night, I thought that while the service was fantastic – I had never seen so many staff in one place at any hospital before – it wasn’t exactly worth hanging around. I decided to get myself organized and formulate the next plan. There had to be a way, I thought to myself, to squeeze just a touch more vacation out of this situation before heading out.

I would have done well to be hired as a chief strategist somewhere. For something. Because I both figured out a plan, as well as a way to execute it. And I had bit of luck, too!

And here's a video from before the accident showing Yvonne happily 'helping' Klaus and Jochen put up the tent: